Surrogates’ Mental Health and Contact with Families 20 Years After Their Journeys

We need more research on surrogacy.

As a physician, I believe that research is the best way to keep the discussion around surrogacy objective, leading to policies and regulation that are based on science and not opinion.

Last November, the first study of its kind was published that followed surrogates 20 years after their journey to evaluate their psychological health and contact with the families they helped.

At Gay Dad Reporter, I feel it’s important to summarize and share new science and research about IVF, surrogacy, and all those involved in these journeys.

Study Background and Design

The recent study was published in the journal of Human Reproduction in November 2025. The authors are researchers from the University of London, Cambridge University, and University College London in the United Kingdom (UK).

The study has been conducted in three phases. The first phase surveyed surrogates one year after delivery. The second phase was about 10 years after delivery, and this publication is for the third phase, which is approximately 20 years after delivery.

While the researchers tried to contact the same surrogates at each time point, this was challenging given the time between surveys. In the first phase, the authors leveraged the only surrogacy organization that existed in the UK, Childlessness Overcome Through Surrogacy (COTS). This organization is still around today. For phase two and three, the authors also worked with Surrogacy UK.

In phase three, there were 21 surrogates who had conducted surrogacy about 20 years previously (range from 13 years to 26 years). They had a total of 71 surrogacy arrangements. All the surrogacy journeys were in the UK with hetersexual intended parents (IPs).

Ten surrogates (48%) had completed only gestational surrogacy arrangements, five (24%) had completed only traditional surrogacy arrangements, and six (29%) had completed both traditional and gestational surrogacy arrangements.

Study Results

The researchers did a thorough evaluation of the surrogates’ mental health through six different, validated questionnaires.

None of the surrogates who completed the assessments of psychological health showed signs of depression. The average score for self-esteem was within the normal range. Additional surveys showed moderately positive emotional balance for the majority of participants. Most surrogates scored within the normal range for satisfaction with life.

Overall: The surrogates were doing very well.

The authors also found that most surrogates were experiencing positive wellbeing that was linked to their surrogacy journey:

‘Indeed, the qualitative analysis of interviews from the present sample showed that many surrogates continued to reflect positively on their experiences of surrogacy with some seeing it as central to their sense of identity.’

For me, the most interesting results were the continued contact that surrogates had with the parents and children.

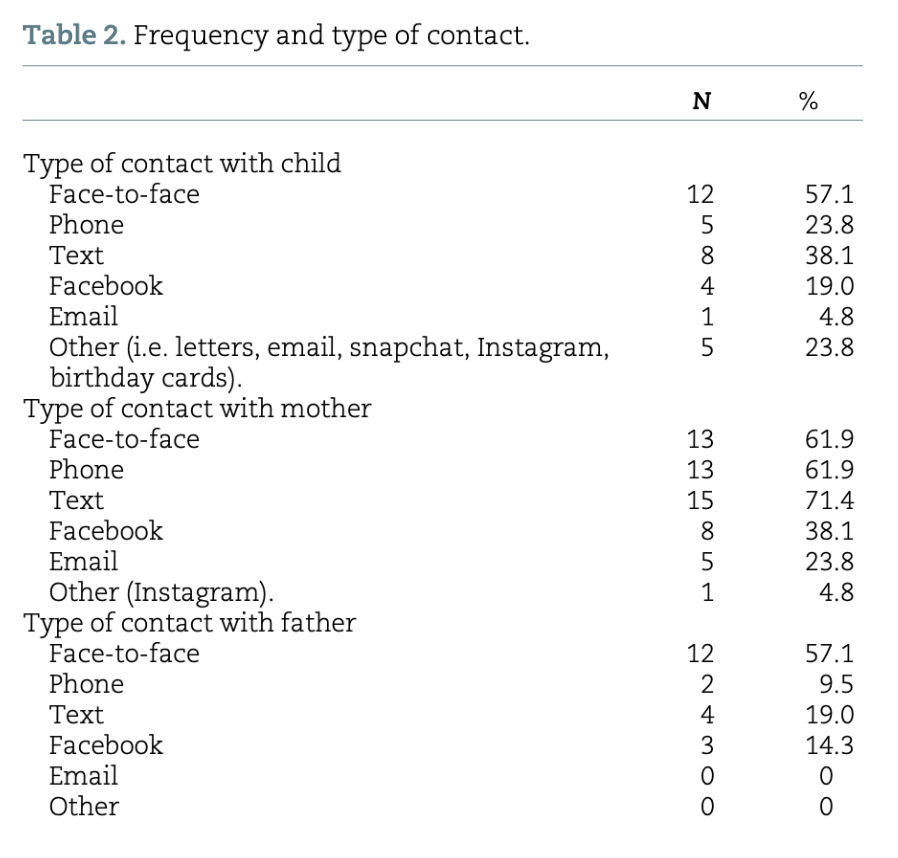

Table 2 from the publication shows the type of contact that surrogates had with the child, mother, and father. While I think there is a bias given that all the surrogacy journeys were UK, I was impressed to see the large percentage of face-to-face contact. There was also a large variety of contact with all members of the family and the surrogates.

Key Takeaways

The study clearly demonstrates that there are no psychological repercussions for surrogates, even 20 years after the delivery. In contrast, there are positive psychological benefits, as the surrogacy journey became an integral part of some surrogates’ identity. Most surrogates maintained strong contact and relationships with the families they worked with.

I appreciate the balanced approach the authors took to this research, as it’s important to note that close contact is not always desirable for surrogates.

‘…as was reported in the earlier phase of the present study, this is not always desired by surrogates. Indeed, the relationships may not be close enough to want to maintain contact following the birth of the child, with the earlier phases reporting that wanting to stay in contact was usually a result of forming a close relationship during the pregnancy.’

Limitations and Further Research

The sample size of 21 is small, which the authors admit is a limitation of the study. It prevented them from additional analyses, including comparisons between different groups of surrogates i.e. those who had carried traditional, gestational, or both types of surrogacy, or between those who were previously known to the couple, i.e. a family member or friend, and those who met for the purposes of the surrogacy arrangement.

The small sample size also did not allow for comparisons of mental health outcomes between surrogates who kept in touch with the family and those who did not. Or, comparing between those that did not want to keep in touch.

An additional limitation is the lack of information regarding the mental health of surrogates prior to their journey or in the years before this survey. A history of mental health or significant life events unrelated to surrogacy could impact their mental well-being. However, this cross sectional survey does not capture that nuance and background.

For me, the main limitation is the geography and demographics of the surrogates and IPs. Surrogacy in the UK is very limited, and a large percentage of IPs now go abroad to Mexico and Colombia. It would be great for future research to examine surrogate outcomes in these other countries, as well as compare domestic to international surrogacy journeys.

Lastly, myself and a growing number of IPs are gay men. It would be great to include this group to see how the relationship with the surrogate is the same or different and what long term outcomes result from journeys with gay intended dads.

There is so much more research that can be done around surrogacy. I’m encouraged to see the great work that these British researchers are doing, and I hope this trend continues with research in other countries to help support ethical assisted reproduction and surrogacy globally.